Texas Colored Congress

The story of the Texas Colored Congress of Parents and Teachers is a familiar one. In 1917, W.S. Benton, a Fort Worth teacher and mother, started a “mothers’ club” in her living room. Around 1910, Texas towns began to roll out strict segregation rules known as Jim Crow laws. Segregation not only impacted students and schools, but it seeped into all areas of public life – restricting the freedoms of people of color.

Public school parents of all races saw this racially charged milieu play out over the majority of the 1900s. W.S. Benton was one such parent (and teacher). Despite the odds, she was committed to making the most out of family engagement and its role in childhood development.

Within a year, Benton gained favor in Fort Worth and, with the blessing of principals and the superintendent, formed a mothers’ club in each public school. As this “council” formed, she rose to become its first president. By 1920, Benton went on to organize associations in five other cities including Dallas and Port Arthur. The efforts of these PTAs helped build schools, form curriculum, buy books, and spread goodwill throughout the state.

On November 24, 1920, each club was asked to send delegates to a meeting of the minds. This meeting marked the beginning of the Texas Congress of Colored Parents and Teachers.

Over the next ten years, the congress would double then triple in size with Marshall, Waco, and Houston joining its ranks.

National Colored Congress

Selena Sloan Butler was a natural leader. When her son Henry enrolled at Yonge Street Elementary School in Thomasville, Georgia, Butler formed the school’s first PTA. In 1919, Butler wrote to the National Congress of Parents and Teachers (NPTA) to inquire about the work of PTA at the national level. Beginning at this time and over the course of 20 or so years, many state congresses formed (with Georgia at the helm and led by Butler). On February 11, 1928, the National Congress of Colored Parents and Teachers (NCCPT) officially established.

Fast forward through wars, the Great Depression, and a couple decades of racial tension, and in 1954, Brown vs Board of Education brought an end to segregation in public schools … at least in theory. An especially bizarre scheme to slow the progress of desegregation is recounted in a fact-finding report from the National Education Association on Desegregation in Mississippi, as follows:

“In [one school] belles to signal class changes ring at different times for black and white students so that even walking through the halls is segregated. The white teachers and pupils in one “desegregated” school are housed in two rooms at one end of the building. The two white teachers, with a total of six white pupils in their classrooms, have no contact with the black principal.” They continue, “At a supposedly desegregated high school, the 40 cheerleaders are white. When one black co-ed sought to become a cheerleader, she was told to come back after she had raised $80.”

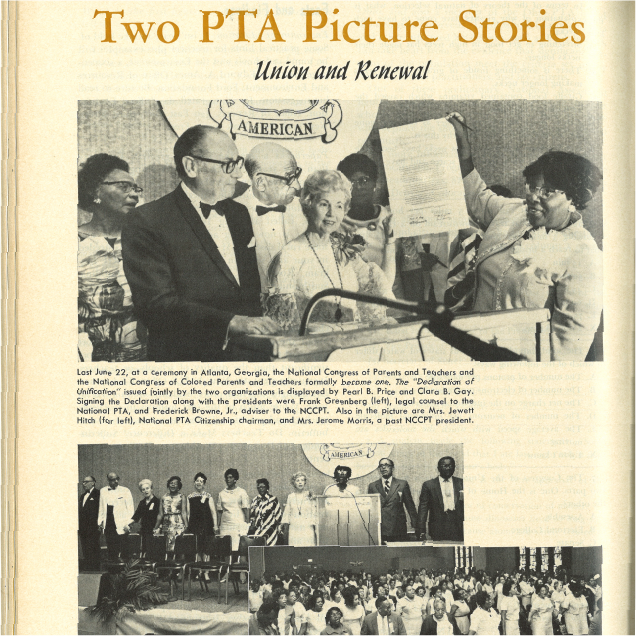

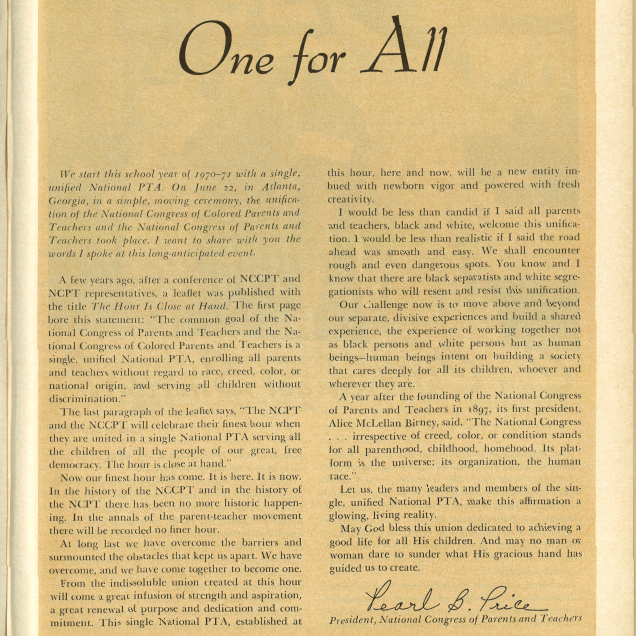

Amid substantial tensions in 1970, National PTA and NCCPT leaders called for a merger of the two organizations. There had been talks for several years and both congresses believed their common goals made this the right thing to do. As the two National PTAs became one, each state was also mandated to merge with its counterpart.

Then National PTA President Pearl Price wrote, “I would be less than candid if I said all parents and teachers, black and white, welcome this unification … Our challenge now is to move above and beyond our separate, divisive experiences and build a shared experience, the experience of working together not as black persons and white persons but as human beings intent on building a society that cares deeply for all its children, whoever and wherever they are.”

This would not be the end of the struggle to achieve true racial, cultural, and administrative balance in Texas and National PTA. Over the years, substantial and intentional efforts were made to drive equality and to oust racial tensions.

Sources

Archives, Texas Congress of Colored Parents and Teachers History, 1961-1968. AR.J.014.

Education, United States Congress House Committee on Education and Labor General Subcommittee on. Emergency School Aid Act of 1970: Hearings, Ninety-First Congress, Second Session on H.R. 17846 and Related Bills. U.S. Government Printing Office, 1970.

Price, Pearl B. “One for All.” The PTA Magazine, September 1970.